4 HP Clift engines waiting for final assembly at the Clift

factory. An educated guess places this photo at about 1918, when

Cliffs small engine sales were booming.

Brass nameplate for a Clift engine. This plate is stamped 5 HP,

even though that size engine was never listed. The engine for this

plate, if it ever existed, is long gone.

As collectors of stationary and marine engines are well aware,

small, low production engine companies abounded across the U.S. in

the first half of the 20th century. As the knowledge and usefulness

of gasoline engines expanded, so did the number of companies making

a bid to enter a potentially profitable industry. Most of these

companies, however, were not only low production operations but

were short lived, as well.

The Clift Motor Company of Bellingham, Wash., was one such

small-scale organization, but it was somewhat remarkable in terms

of its longevity. From its beginnings in 1913 and through the

1930s, the firm turned out a variety of marine engines ranging from

4 HP to 100 HP, building as many as 5,000 to 10,000 engines,

although the exact figure is unknown.

Clift Engines

Large, multi-cylinder Clift engines featured post construction

and were produced in the open crosshead (also referred to as a

‘T’ head) form. They featured crankshaft splash shields and

could be furnished with air starters. In the first five years of

production the company emphasized its heavier engine lines, but

after 1918 production of its smaller engine line boomed, with

smaller engines produced at a rate of approximately 60 units per

month. These smaller engines were produced in 4 HP and 7 HP sizes,

and cylinders could be doubled to yield 8 HP or 15 HP. Clift

engines used Model T Ford pistons, connecting rods and valves. The

economy of this practice meant the smallest engines could be sold

for $150, including clutch and propeller.

In addition to being sold under the company name, many Clift

engines were jobbed out and sold as other marques, such as

‘Standard Kid and Fish Skiff Special.’ In his advertising

for Clift engines, plant manager Comely Clift reminded potential

customers that the company deserved credit for having built far

more engines than those actually bearing the Clift trade name. As

one ad stated: ‘We realize further that we have overlooked the

advantage in failing to properly identify our trade name in the

production of the hundreds of engines now in service.’

Push for Numbers

Introduction of the smaller Clift engines coincided with a

company announcement in 1919 that it was about to ‘enter a

vigorous campaign … to establish (the Clift) trademark and the

quality of the engines in the minds of the boat owners of the

country.’ The company, according to the December 1919 issue of

Pacific Motorboat Magazine, was ‘undoubtedly the largest plant

on the Pacific Coast devoted exclusively to small engine

production.’ With an eye to increasing sales, the company

advertisements reminded readers that, ‘Some good territory is

still open to responsible agents,’ as well as the less

restrictive ‘Live Agents Wanted.’

Despite the economic slump that followed World War I, sales

appear to have been vigorous, with reported sales of blocks of 30

to 50 units to Pacific coast cannery fleets. Engines were

reportedly marketed to fishing interests as far away as Sweden.

With their four-cycle design, Cuno timers and Schebler

carburetors, Clift engines earned a good reputation for durability.

Mechanical troubleshooter Frank Clift, brother of company founder

Comely Clift, attended to the occasional local breakdown. Every now

and then, needed repairs went beyond the ordinary. Former company

employee Bill Hays, who passed away in the early 1990s, told of a

local Japanese fisherman who installed a Clift engine in his skiff

and departed, only to return several months later to report,

‘Engine sick, it go bump, bump, bump.’ Inspection revealed

that the engine, though well lubed when it left the factory, had

never been topped with oil and had long since run dry. On teardown

the bearing babbitt was found to be long gone, and the crank

journal had been reduced to the thickness of a lead pencil.

Amazingly, the engine still ran in this condition.

One of the Clift engines built by students at Bellingham (Wash.)

High in the early 1950s. The intake and exhaust ports were reversed

on these last engines, which also featured a counter-balanced

crankshaft.

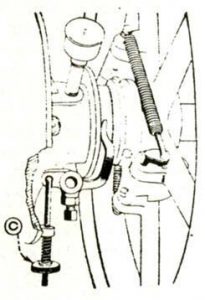

An original Clift 4 HP engine, serial number 1482, date unknown.

Clift 4 HP engines used Model T pistons and rods and had a bore and

stroke of of 3- inches by 4- inches.

Another Clift 4 HP engine. Note the spark plug mounted in the

side of the cylinder instead of the top of the cylinder head. Clift

made numerous changes to the 4 HP engine line as it evolved.

Photographs show the company plant on the Bellingham waterfront

as being rather typical for the times, with multi-paned windows, a

barrel stove for heat and some 30-plus engines on the floor ready

for shipment. According to former plant employee Hays, his wages

grew from 25 cents to 60 cents per hour in the years between 1917

and 1925 as he progressed from fledgling to full machinist. He

reported that approximately 15 men worked in the shop at any one

time. By the 1930s, however, the Clift motor works apparently

reduced its operation to machine work and Clift engine repair,

perhaps having fallen victim to Depression-era economics. It’s

thought the company continued in this capacity until the early

1940s when it ceased operations all together.

The story of Clift engines however, was not yet over, for as

late as the early 1950s Clift engine castings were being machined

in the Bellingham High School shop as student projects. In the

early 1950s machinist Bill Hays, who worked at the plant through

eight of the years of peak production, landed a job as shop teacher

at Bellingham High School. Under his direction, several students

obtained castings from the original patterns, machined the parts

and completed four 4 HP Clift engines. These final products

differed little from the pre-World War I models, although at least

one had a counterbalanced crankshaft for smoother running.

Though they are not overly plentiful in Pacific Northwest

collections, an occasional Clift appears in a marine museum or at

an engine show. The usual problems associated with salt water

deterioration have, no doubt, cut down on the number of running

examples. Interestingly, many of the original casting patterns were

only recently discarded by the Onion Foundry of Bellingham, Wash.,

which did casting work for Clift Motor Company. Some of these were

owned and displayed periodically by a local maritime heritage

group.

Contact engine enthusiast Earl Bower at: 417 E. Hemmi Road,

Lynden, WA 98264, or e-mail: res1tazc@veri-zon.net

Contact engine enthusiast Chuck Zeiger at: 707 Poplar Drive,

Bellingham, WA 98226.